The Foreign Service at 100: My time on the front lines of diplomacy

In 2007, I joined a roomful of Americans from all walks of life — teachers, veterans, first-generation immigrants, journalists, academics, photographers — who took the oath of office to serve and protect the United States as diplomats. Before we met, many of us had little in common. Some of us were in our 20s. Others were beginning a second career. All of us — along with our families — shared a sense of pride, and jitters, about the new journey we were about to begin.

WWII Victory Day commemoration

Almaty, Kazakhstan, 2017

My Foreign Service class reflected America’s diversity and dynamism because 100 years ago this month, in May 1924, the US Congress transformed our diplomatic corps. With the passage of the Rogers Act, any American citizen could apply to be a diplomat through a rigorous (some say infamous) written and oral exam.

Today, about 15,000 diplomats are spread out over 270 embassies and consulates, many of them remote. With less than 1% of the federal budget spent on international affairs, our diplomats defend American interests and values, serve American citizens in need, and build the partnerships we need to outcompete Russia and China. I was lucky to be a member of the Foreign Service family, serving in Sudan, Tajikistan (twice), Afghanistan, and Kazakhstan.

My path to the Foreign Service began on a September morning in Kentucky, when my mother called and told me to turn on the television. Like many people on 9/11, I learned how connected America is to people and events on the other side of the world. I decided I needed to meet some of those people, so I joined the Peace Corps. A few months later, I was in Kazakhstan teaching English at a village school, eating horsemeat, learning Russian, and forging friendships over tea (or vodka). From schoolkids to grandmothers, everyone wanted to learn more about America and the opportunity it represented. After two years in Central Asia, I was hooked. I took the leap to apply for the Foreign Service.

New Foreign Service Officers can expect challenging assignments. Mine was Sudan as the consular officer responsible for serving American citizens in need. For me, the job was tough. My brilliant USAID colleague John Granville, an Africa specialist, made it look easy as he led a program to connect South Sudanese communities with solar radios. In the early hours of January 1, 2008, we attended the same party as four men prowled the night looking for Americans to kill. John’s car happened to be the first car they spotted. They opened fire, killing him and another colleague, a Sudanese driver named Abdel Rahman Abbas.

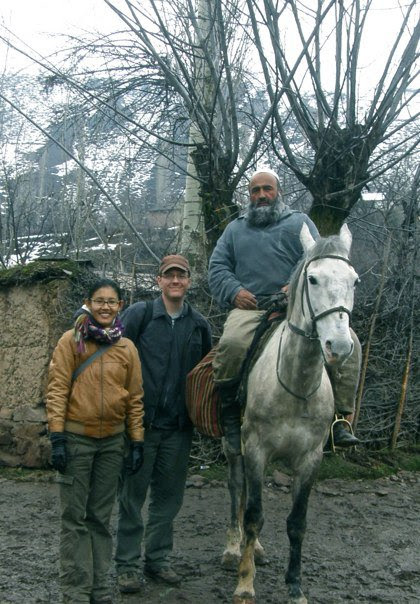

Mountain diplomacy in Tajikistan, 2010

Diplomats serve in war zones armed with little more than a notebook and a pen. In Kabul, my colleagues and I lived in a walled American compound, but entered Afghanistan as soon as we left the barricaded gate. With my unflappable Afghan assistant, Shinwari, I had the privilege of meeting imams, tribal leaders, activists, and political elites to gain insights that only come through personal relationships. I also had the privilege to meet Anne Smedinghoff, an ambitious second-tour press officer committed to engaging people outside the wire. Anne was doing exactly that during a visit to Zabul Province — delivering science and math books during a visit to a local school — when a suicide bomber killed her, three US troops, an Afghan interpreter, and Afghan civilians.

After years on the frontlines of the war on terror, Russian’s hybrid invasion of southern and eastern Ukraine awoke the Foreign Service to renewed threats from Russian influence operations. As “little green men” began raising Russian flags in Crimea, I was pulled onto a ragtag taskforce of Russian speakers to help expose their activities in real time. We soon realized that countering disinformation was not enough; we needed to take America’s message directly to Russian speakers. While serving as a Public Affairs Officer in Kazakhstan, I got a call asking if I could travel to New York immediately. A few days later, after feverishly memorizing talking points on the plane, I was standing in UN Plaza as the US government’s first Russian-language spokesman at the UN General Assembly.

As a civilian, I used to believe that someone, somewhere in government had the answers and knew what to do when a global crisis struck. My years in the Foreign Service revealed truths that were as inspiring as they were terrifying: American diplomats are people doing the best they can with limited information, in dangerous environments, often with limited or no resources, forced to adapt and pivot as threats and policies shift around them. Despite these challenges, I saw my colleagues — and their families — remain steadfast in their commitment to the values that have united Americans since the Foreign Service was founded 100 years ago.

American diplomats represent all of us. We all have a stake in helping them succeed in their missions on behalf of our country, our values, and security. As a member of the Spirit of America team, I’m proud to continue being a part of these missions, leveraging the power, resources, and private capabilities of the American people to support their work on the front lines of diplomacy.

Chaz Martin, a former US diplomat with 20 years of government, private-sector, nonprofit, and development experience, became Spirit of America’s Director of International Communications in 2023. As a Foreign Service Officer, Chaz was named the Department of State’s Linguist of the Year in 2016 for his work combatting disinformation.